- Home

- Edna Fernandes

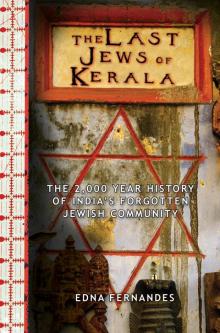

The Last Jews of Kerala Page 14

The Last Jews of Kerala Read online

Page 14

“Back in those days before the change, the Blacks were forced to sit on the ground outside. Well, Salem wasn’t going to take it any longer!” The old man’s eyes sparkled as he recalled Salem’s audacious plan to enter.

“What happened was he started to sit under the window sill looking into the synagogue. Then on the sill. Body was on the sill, but his legs were technically outside. That’s how it began. Slowly, he put one leg inside, then the other. These people had no guts to stop him. Then slowly, he came inside and sat there and so it went on. They couldn’t stop him,” he shook his head as he laughed and wagged his finger. “They couldn’t stop this man, they simply looked daggers. He then started taking his sons with him. He was a very strong man and they were scared. He was a top lawyer, a writer, he knew Gandhi, he knew Nehru. Salem was our Jewish Gandhi.”

Salem did not stop there. He wanted every Jew to have access to the Paradesi Synagogue, the weak as well as the strong. He held full prayer services at his home or joined the prayers at the homes of other Blacks who could withstand the humiliation of the synagogue apartheid no longer. Through such small acts of defiance, Salem effected great change. He skillfully articulated the Black cause, combining his devastating lawyer’s logic with a rousing oratory that began to sway younger, more modern thinking members of the Paradesi community. A small number of Whites became convinced that segregation was wrong.

These younger, progressive Whites joined his campaign for change and their support proved to be the vital tipping point which would lead to a revolution on Synagogue Lane. Inspired by Salem, young White Jewish men used their own methods of non-violent protest. They refused to carry the heavy Torah scrolls during the Simhat Torah processions until change was introduced. Their revolt led to a breakthrough—eventually two benches were set up for the Blacks in the back of the Paradesi Synagogue. They were just two small benches at the back of the synagogue. But for the first time in four hundred years, the Black Jews were inside. They had moved from the floor of the anteroom to a ringside seat at the heart of religious proceedings. In 1937, the academic and longtime observer of the community Mandelbaum visited and reported an astonishing change: Blacks could read from the Law on weekdays, although not on Sabbath.

Still, Salem was not satisfied. Blessed with formidable patience as well as a ferocious intellect, he relentlessly chipped away at the edifice of prejudice, piece by piece, until it came tumbling down. In 1942, a satisfied Salem recorded in his journal:

“For the first time in the History of the Paradeshi Synagogue I got the chance, by stressing the law of the religious services regarding the reading of Torah, the privilege of reading the Maphtir of this Sabbath and Rosh Hodesh. May God be praised . . . May the innovation become the order of the day!”

This was the closest the understated Salem got to trumpeting Black Jewish religious emancipation. Yet his exclamation mark at the end of that sentence speaks as clearly as any victory speech of the joy that must have overwhelmed his heart that day. It was just the beginning, as he envisaged. By the close of the decade, there were further landmarks on the road to equality. The Blacks could bury their dead in a separate area of the Paradesi Synagogue cemetery. Blacks and Whites were still not allowed to lie side by side in death, but at least now they could share the same soil. But, most important of all, Black Jews could be called to read Torah on Sabbath and recite blessings.

Yet there was still a way to go. Blacks were barred from holding weddings or circumcisions in the Paradesi synagogue. These had to be conducted at home. Also, marriage between Black and White was still prohibited.

The coming decade would see great change sweeping through Cochin’s Jew Town and for Jews worldwide. On the global stage, the world saw the birth of Israel in 1948, which triggered a wave of mass migration of Jews everywhere. The founding fathers of Israel wished to create a rainbow nation, where the Diaspora of every hue and nationality could reunite in their ancient land once more. The idea of Jews of every color coming together to summon up a nation state from the desert sands was a powerful one which, no doubt, inspired further change for the Black and White Jews of Cochin. After all, in the motherland itself every Jew—regardless of color—played an equal part in nation-building.

Within a few years of the creation of Israel and the Blacks winning equality in the Paradesi Synagogue, the last taboo was broken by a passionate affair between two young lovers, Balfour and Baby. Their love is the final chapter in the story of apartheid in Cochin’s Jew Town. It took Salem’s oldest son and his beautiful and spirited bride to bring the era of segregation to a close. Theirs was a final conflict between love and prejudice. And in keeping with all great romances, prejudice was vanquished. Love won.

* * * *

CHAPTER NINE

Taboo Love

“My dove, your splendor resembles Orion and the Pleiades And I, for love of you, shall sing a song.”

—SIXTEENTH-CENTURY POEM BY ISRAEL MOSES NAJARA, SUNG BY COCHINI JEWS

Wedding fever had gripped Synagogue Lane. A flutter of creamy manila envelopes arrived in the post pronouncing the forthcoming nuptials of the young couple. On hearing the news, for a moment I envisioned some Hollywood-style ending, a sigh-inducing rapprochement in the long running saga of Yaheh and Keith. Had cold indifference graduated to slow burning pragmatism? Had the elders finally bent them into submission or had they decided over too many glasses of “petrol” toddy they would sacrifice themselves to save two thousand years of history after all?

“Don’t be a damned fool,” said Gamy, as if I’d suggested sun and moon could dance in the same sky. “Balfour and Baby’s grandson is getting married in Israel. A nice Jewish girl. Reema, Sammy and Queenie fly out in a few days.”

The wedding would be held near Haifa, close to where Baby continued to live after her husband died. There would be no wedding ceremony in Cochin—the last one had taken place generations ago. Still, a wedding was a wedding and if the couple would not come to Cochin, then a banquet would be held in their honor.

The news had the desired effect: the Paradesis walked around with smiles on their faces and it was good to see. A wedding was a time to rejoice and forget the past few weeks, burying Shalom, the stress of organizing the festival season. Forget the difficulties of the past years, indeed. Those attending were in a whirlwind of preparation and those remaining were planning the finest party Jew Town had seen in a while. The couple would be toasted from Israel to India.

“Since your Enemy Number One is flying to Israel,” suggested Gamy, “you shall come to the party. Johnny’s house, Wednesday, eight o’clock. Just don’t tell Sammy.”

Sammy, Queenie and Reema would be flying first to Mumbai where they would change flights for Israel. Gamy had already been in touch with Indian Airlines and El Al over the arrangement of wheelchairs to take them through check-in and security. The three of them would need an additional entourage of baggage handlers to deal with the accompanying luggage. I watched in bafflement as Gamy, Reema and old Mary grappled with a dusty brown leather suitcase that had been hauled out of storage for the occasion, and began to pack.

It was the arduous task known to every Indian family, Jewish or not. I had learned from my own family that Indians never travel lightly. The concept of capsule packing is unknown in the subcontinent. Even the shortest of trips required certain essentials: a choice of heirloom jewelry for parties, gifts for the elders, mangos by the box-load, one small bag of superior quality chapatti flour, one kilo each of garam masala, cumin and coriander seeds, chocolate and toys for all the children. And pickle.

Gamy deliberated momentarily over whether the family in Haifa would require dried fish as well, or whether pickle was an adequate condiment option. The packing naturally took days to complete. At one stage, Gamy could be seen throwing small Indian dolls across the parlor floor, raging that he had specifically requested small easy-to-pack toys, not fullsize action heroes. The night before departure the brown suitcase sat in the entrance hall, strai

ning at its zipper like a squat Indian gentleman suffering from explosive indigestion after too much butter chicken. For the first time in my life, I pitied the immigration customs officers at Ben Gurion International Airport. They would need a bigger table.

* * * *

Sammy, Queenie, Reema and her suitcase of never-ending treasures departed for Israel. As their white ambassador taxi disappeared from view, Gamy had a look on his face which said, “Let the drinking commence.” The men quickly got down to doing what men do best—they carefully judged the amount of whisky that needed to be purchased and consumed that evening. Did the occasion merit just plain Indian whisky or should a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black Label be procured? Such weighty debates went on late into the afternoon. Meanwhile, the women got together, jotted down a menu, shopped and then cooked up a storm under the leadership of Johnny’s wife, Juliette, who was widely acknowledged as the best cook on Synagogue Lane.

The party would be held at their house, the Hallegua mansion right at the top of Synagogue Lane. Johnny insisted that as the senior-most elder in Jew Town after Sammy’s departure, he would take care of the celebrations. He refused to accept payment or help and Gamy was grateful as it was surely a cost he could ill afford. Everyone was invited. The last Jews of Kerala would gather that evening to celebrate the wedding of the grandson of Baby and Balfour, the first couple to unite the two communities. The only non-attendee was Sarah, who was still in mourning for Shalom. But even she would not miss out on the feast as Juliette had arranged to send her a plate of food. With the solemn presence of the patriarch gone, the mood became light, almost frivolous. Then just before sundown everyone disappeared back into their houses to say evening prayers and get ready.

As I approached the Hallegua mansion that evening, it was unnaturally quiet. I knocked at the door and it opened a crack, just a sliver of light and one eye was visible. It was Yaheh who looked surprised to see me. She had that stern look on her face again.

“Hi, I’m here for the party.”

“What party?”

“The wedding party.”

“What wedding?”

She was good. She didn’t even blink. In a parallel universe she would have been the most sangfroid poker player in Vegas. I could imagine her celebrating in the bar after breaking the house, taking to the stage and belting out Bette Midler show tunes.

“Your father and Gamy invited me.”

The door closed. A minute passed, then it swung wide open and the doorway suddenly flooded with yellow light, bathing me in conviviality and the distant sound of singing from the back of the house. Yaheh smiled broadly. Not a fake, tight smile, but a real beamer, full of pleasure.

“Come in. You’re very welcome in our house. Let me take you through.”

She was transformed by the occasion: not just in demeanor but appearance too; she was wearing light makeup, lipstick-mouth like a summer strawberry and dressed in a rainbow silk kaftan that rippled color as she moved. She led me through the old house, suddenly effusive with pride and hospitality. The entrance parlor was a grand room with dizzily high ceilings and wonderful mosaic floors made for waltzing. Antique carved furniture adorned the room and a television set buzzed away in the corner as some of the young men from Ernakulam watched the cricket, periodically shrieking their delight. The house was almost three hundred years old and its original character very much unchanged. The cracked plastered walls breathed memories of the past sorrows and celebrations of the White Jews and I wished I could discern their secrets. From the salon we walked through to a long corridor. Seated on a pew alongside one wall were the ladies, all attired in their finest outfits, primped and pretty as if waiting to be asked to dance.

The aunties cooed their welcome as Yaheh introduced me. Most of them, I already knew. The older ladies wore embroidered chiffon saris in the colors of Kerala: petrol blue, lime green, dusty pink. Gold bangles jangled on their arms as they carefully smoothed down their dark hair, polished and perfumed with coconut oil. Dangling earrings swung from their ears as their heads turned from side to side in conversation and many wore the traditional Jewish wedding necklace. There were just a couple of young girls from Ernakulam, shy and awkward, in trendy Westernized clothes, sipping cola and squirming with displeasure as their mothers fussed over them. Juliette and Yaheh ran the proceedings with effortless aplomb, keeping the conversation, food and drink flowing. The table opposite was laden with sodas for the ladies, whisky, beer and rum for the men who were all gathered in the dining room to the left of the corridor. Raucous laughter and a hybrid of Malayalam and Hebrew burst from the open doorway, punctuated by quavering snatches of old Jewish songs. They sang of love, of marriage.

A slightly giddy Gamy tottered over. His glasses had slipped down his nose and his long front teeth seemed to have lengthened with the influence of drink. Armed with a Coke, he led me into the dining room where I sat next to him, Johnny and Isaac Joshua from Ernakulam. By the look of them all, either I was very late or they had started very early. Around thirty men, Black and White, Indian and foreign guests, sat around the huge table that was used for formal banquets. A Star of David light twinkled on the wall opposite. The men started another round of singing, thumping the table as they sang, each trying to outdo the other, even the gentle Isaac Ashkenazi joined in, never happier than when he was surrounded by rowdy male company and safe from the perilous grasp of predatory females. In the absence of Sammy, Isaac from Ernakulam led the festivities. In a room full of voices, his bellowed the loudest.

The ladies flitted in and out, bearing great platters of hot food, a fabulous spread of tongue-lashing chilly chicken curry, delicately spiced kidneys with onion, tomato and finely chopped dhania, rice, salads, pastels and pickles. In the name of a couple far away, a couple most had never met, they united in celebration. Isaac ordered a replenishment of plates and glasses. Then in the soft haze of satisfaction, it was time for the community to offer prayers for the couple. Unsteadily he rose to his feet, passed his hand over his smooth bald head as if for good luck and began to read from the Torah, voice trembling with the melody of its meaning. His audience was overcome; a couple of the men snuffled into their hankies. It cannot have escaped them that this was a wedding that should have taken place in Cochin or that there never would be another wedding on this street in their lifetime or their children’s. Isaac led the prayers for more than thirty minutes. Gamy, ever the provocateur, said he couldn’t remember all the words, only to receive a look of severe remonstration from Isaac which was enough to bend him into submission. For this was the nature of family: united in a tumultuous shared history, yet distinct in nature and temperament; rousing camaraderie one minute and irritating the hell out of one another the next; capable of love despite having hurt one another. For the first time since I arrived in Cochin, that night around Johnny and Juliette’s table the Black and White Jews were one, grievances forsaken like false lovers and the past a forgotten territory. There could be no better wedding gift for a young couple in Israel.

* * * *

As the men sang late into the night, the women remembered weddings past. They were no different to womenfolk of any community: talk centered on what outfit the bride might wear, the ceremony and love songs. I looked at Juliette, who was happy that the party had been successful, cheeks blushed with pleasure. Her daughter Yaheh also seemed very much at peace as she gently stroked Baby Doll’s fur and laughed with the others. Keith had not come that night, nor his brother Len. Pretty much everyone else was there, yet they remained the invisible men of Synagogue Lane.

In the old days marriages were arranged and there was little say in the matter for the youngsters. It was the Indian as well as the Jewish way then. Once the bride’s family had received a proposal and accepted, the people of Jew Town would gather and summon the couple to its presence. The foremost elder would ask the groom if the match met his parents’ wishes and then he would ask of the young man’s own wish, to which he replied simply: “I desire her.”

Once the engagement was toasted, the women would bake sesame cookies as a symbol of fertility and a wedding date was fixed. In the community’s heyday, it was said that the bridal outfit of the Cochini Jews was known for its exceptional finery. The fabric for her skirt was silk lined with cotton, stretched tight on a wooden frame and hand-embroidered by the Muslim dressmakers who were known for their intricate needlework. The wedding blouse was sheer white muslin, edged with gold, and upon her head the bride would wear a cap decorated with more gold jewelry or embroidery. On her neck she wore the kali mala, a heavy beaded necklace made up of pearls or gold coins or sometimes squares of turtle shell. Before the wedding, the local goldsmith would come to the bridal home and in the presence of the couple and their families he would fashion the ring from a gold coin provided by the groom’s father. The traditional Hindu bridal necklace, the tali mala, made of gold and inlaid gems, was then clasped around the bride’s neck by the groom’s sister. This was one Hindu custom that the Kerala Jews adopted.

The road to the synagogue was spread with coconut branches and men were hired to beat drums, while troupes of Hindu musicians played Jewish wedding songs. The Jews were just one strand of the many religions that had been woven into Kerala’s multi-faith history. In Cochin, the Muslim would painstakingly sew the Jewish bride’s blouse, while the Hindu would lend his music and song to her wedding procession.

The ceremony took place in the synagogue. Before the groom left his house a lump of sugar was placed in his mouth, so he may always taste the sweetness in life. He would arrive at the synagogue at the head of a procession with a parasol over his head or sometimes hoisted on the shoulders of friends, accompanied by whoops of joy, the rat-tat-tat of firecrackers and lighted torches. The groom was also dressed in white, with a gold-embroidered kippah and a garland of flowers around his neck. Years ago, the groom would be attired in a Baghdadi-style silk kaftan and white turban. At the synagogue he was received by guests who showered him with bright green leaves and tiny coins.

The Last Jews of Kerala

The Last Jews of Kerala