- Home

- Edna Fernandes

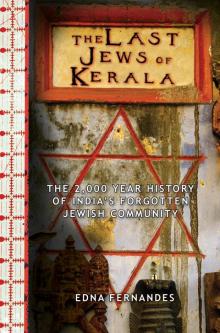

The Last Jews of Kerala

The Last Jews of Kerala Read online

ALSO BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Holy Warriors

Copyright © 2008 by Edna Fernandes

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data

Fernandes, Edna.

The Last Jews of Kerala: The Two Thousand year History of India’s

Forgotten Jewish Community by Edna Fernandes

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60239-267-0 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-63450-271-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-62636-935-1 (ebook)

Printed in the United States of America

To Felix, with love.

CONTENTS

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

The White Jews of Synagogue Lane

CHAPTER 2

King of the Indian Jews

CHAPTER 3

The End of Shalom

CHAPTER 4

The Gentle Executioner

CHAPTER 5

Land of Black Gold and White Pearls

CHAPTER 6

Opium Traders and Oil Pressers: The Lost Tribes

CHAPTER 7

Son of Salem

CHAPTER 8

Segregation in the Synagogue

CHAPTER 9

Taboo Love

CHAPTER 10

“A Wife Who Will Not Give Me Headache”

CHAPTER 11

Roses in the Desert

CHAPTER 12

Home

Acknowledgments

List of References

INTRODUCTION

“Our Days Are Like Passing Shadows.”

—PSALM 144:4, INSCRIPTION ON THE PARADESI SYNAGOGUE CLOCKTOWER IN JEW TOWN, MATTANCHERRY

The last of the summer monsoon rains had passed. Bruised grey skies and merciless sheets of black rain yielded to freshly-washed vistas of blue and green. Coconut palms sashayed in breezes that blew inland from the Arabian Sea, bearing the taste of salt and smell of fish. Jackfruit and papaya trees shimmered in the sunlight as crows feasted on fruits shed onto the grass below, beaks disgorging seeds and bleeding sweet dark juices into the soil. As the humidity rose, jewel-like flowers of pink and red drooped from branches that encircled the cemetery stone walls. Cochin had burst into renewed life.

Skin slick with sweat, the gravediggers completed their task and gathered up the shovels to withdraw before the funeral. With their departure, only the parakeets were left to pay their respects from a vantage point high in the palms overlooking the old Jewish cemetery, yellow eyes transfixed by the mawkish scene below.

It was September 2006, the burial day for Shalom Cohen, last of the priestly line of kohanim in Cochin and one of the dwindling Diaspora tribe known as the White Jews of Kerala. With his death, just twelve remained. An ambulance stopped at the gates of the cemetery, followed by a group of mourners dressed in spotless white. In keeping with Cochini custom, Psalm 91 was sung to relinquish custody of the body to God:

“No disaster shall befall you,

No calamity shall come upon your home.

For He has charged his angels

To guard you wherever you go,

To lift you on their hands

For fear you should strike your foot against a stone.

You shall step on asp and cobra,

You shall tread safely on snake and serpent.”

The last of the White Jews chanted their lamentations as they approached the graveside, faces the same color as their vestments, hands raised in supplication to indifferent blue skies. Shalom’s body had been purified through the cleansing ritual before being dressed in a simple white shroud. Earth from Jerusalem and from Cranganore, the ancient Jewish kingdom of Kerala, was placed in his eyes and mouth. His head was swathed in strips of white linen, his corpse sprinkled with rose water, an old Sephardic custom, and then he was laid in a wooden coffin bereft of all adornment.

The coffin was carried on a palanquin by bearers to the site of the grave, the procession stopping seven times along the way to mark the seven references to the word “vanity” in Ecclesiastes. Winds rushed through the towering palms, their treetops bowed as if in deference to the occasion. As the parakeets sang their own plaintive tribute, the coffin was lowered into the ground, entombed within the red earth. Once the ceremonials had been completed, the bereaved left the graveside throwing fistfuls of dust and torn grass over their shoulders to symbolize the tearing of their hearts. The funeral had shaken this tiny community, which is all that remains of a once splendid history that crossed centuries and continents. To those present, it had been a terrible epiphany: with the death of Shalom, the demise of the last Jews of Kerala no longer seemed an event fixed far into an intangible future, but an inevitability with shape and form, casting its promise of foreboding upon them all.

* * * *

I came across the Jews of Cochin on my first visit to Kerala in 2002. While working on a story about tea plantations I chanced upon Synagogue Lane, home to a diminishing group of white-skinned Indian Jews who claimed a lineage dating back to the era of Solomon.

Then, as now, they were defensive, introspective and wary of strangers to the point of paranoia. The White or Paradesi Jews claimed they were both the only Jewish community remaining in the whole of Kerala and the Jewish community with the oldest history in India. In many ways they were typically Indian, yet they retained an ethnic and cultural distinction that was unmistakable. The men and women wore sparkling white lunghis and saris, ate Jewish-Indian food with their hands, even adapted some of the Hindu customs to their way of life, but they remained orthodox in their Jewish beliefs, and their fair skin made for an arresting contrast to the polished ebony complexion of the Keralites. In gleaming garments they wandered through Jew Town like ghosts communing with the living. Back in 2002, the elders still harbored hopes of saving the future generations by pressuring the last young Jew and Jewess among them to marry, deploying the most devastating of weapons in their arsenal of persuasion: guilt, on an apocalyptic scale. “Marry, bear a child. Or the end of thousands of years of Jewish history rests on your heads,” they told the youngsters. The brinkmanship failed and the fate of the White Jews was sealed.

Within the mosaic of histories of the subcontinent, theirs is a story easily overlooked and yet the Kerala Jews remained indelibly fixed in my mind: a people who vanquished the treacheries of history, fled Israel after the destruction of the beloved Second Temple and later escaped the horrors of the Inquisition in Europe to build a new life in India. Then, when all seemed safe, when they felt assured they were beyond the grasp of extinction, circumstance delivered them to danger once again. What is it like for a people whose end has come?

Imagine if one had been able to witness the end days with the people of Easter Island, the Mayans of Central America or others whose civilizations suffered such precipitous downfalls, leaving behind ruined temples as inadequate tributes to what once w

as. In the book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, Jared Diamond writes of such civilizations, how they often wittingly contributed to their own disastrous decline and how the evocative ruins they left behind continue to mesmerize us: “We marvel at them when as children we first learn of them through pictures. When we grow up, many of us plan vacations in order to experience them firsthand as tourists,” he said. “We feel drawn to their often spectacular and haunting beauty and also to the mysteries they pose.”

Such mysteries as did they know they were courting destruction and if so why did they continue? Their ruins are not mere archaeology, but warnings that cry out from the past, symbols of societies that once seemed invincible and yet precipitated their own demise. As I walked amidst the ruined synagogues in Cochin or even down Synagogue Lane, thronging with Nikon-toting tourists, evidently these were not grand temples marking a mighty civilization. Yet on a very modest scale, they were the poignant remains of a nonetheless remarkable and ancient people who dated back to the era of the First Temple, according to their oral history.

They had survived the worst that could be thrown at them—tyranny, dispossession of a nation, the razing of their seat of worship—and yet endured to refashion their community amid the tamarind trees and jasmine blossoms of India. Unlike Diaspora elsewhere in the world during history, the Jews of Kerala were a feted people, embraced by neighbors of all creeds. While other faiths in India were susceptible to the sinister seductions of communal violence, the Jews of Kerala remained immune to the troubles that periodically threatened to endanger India’s delicately poised religious equilibrium. Part of the reason for this was sheer lack of numbers: they were simply too small in number, too insignificant a lobby to be perceived as a threat to Hindu, Muslim or Christian. They were never a proselytizing people but cultural chameleons who adapted easily. Over the centuries they proved to be exceptionally adept at surviving the volatile shifts in the political order of the region, from the Cochini royal dynasty to the Portuguese, Dutch and British invading colonial powers.

Despite every advantage, in the end they were undone not by anti-Semitism or war, nor pestilence or the vagaries of nature, but at the hands of one another as they allowed dissent and rivalry to breed within their ranks. That divide was institutionalized in apartheid between Jews of different skin color in Kerala and meant there were ultimately too few marriages, too few children and, therefore, no future. When the state of Israel beckoned in 1948, many answered its call and left behind a redundant few.

Like other lost societies, today’s visitors to Cochin are also lured by the romance and longevity of this history and as they take their snapshots, one can see that the Jews of Kerala have already become a souvenir people. Soon their story will also be immortalized on key-rings and other collector’s items. Already, we are within the epilogue of one of the great stories of the Jewish Diaspora, an epic which will end in Kerala in our lifetime, perhaps within a decade.

For these reasons, I went back in the autumn of 2006. I was pregnant with my son at the time, which made me particularly attuned to the sensitivities of a community that had not celebrated a birth for decades. On my return, I discovered that the White Jews were not in fact the only Jewry left in Kerala. There was another equally small community across the waters called the Black Jews. The Black, or Malabari Jews as they were also known, was a distinct group that lived in the main town of Ernakulam, as well as the nearby villages of Chennamangalam, Mala and Parul, which are all within a few kilometers. They were known as the “Black” Jews because of their darker coloring, which was the same as that of the indigenous Keralites, a skin color that told its own tale of historical integration with the Indians and marriage to converts to Judaism.

The two sides, the Blacks and Whites, had suffered a bitter feud for centuries, their relations marked by apartheid, discrimination, claim and counter-claim over who arrived first in India, who could claim common ancestry with the Jewish founding fathers of the subcontinent and who could lay claim to religious purity. In Hindu-dominated India, a country where purity is paramount and bestows ascendancy in the social hierarchy as well as political and economic privilege, these were not petty concerns but the very foundation of one’s survival. The stakes were high and history showed that neither side—Black or White—was willing to relinquish their claim. This lay at the heart of the split within the Jewish community, evident for the last four centuries, polarizing them when there should have been much more to unite them. It also proved to be their undoing in the end.

Where together they once numbered in the thousands, with eight synagogues and vast estates of plantations and houses that stretched across the tropical coastal plains of Cochin, today there are fewer than fifty Jews, and just one working synagogue remains with not enough men to form the quorum needed for prayer on Sabbath. The other synagogues have fallen into disuse, crumbling into dust, annexed by jungle and home to nests of cobras.

The story takes us on a voyage from King Solomon’s Israel to the west coast of modern-day India, moving between the great intercontinental migrations of early modern history and the tragicomic feud of Jew Town that has brought Kerala’s Jewry to its knees. At its heart is the battle for racial equality in the backwaters of India, an ancient civil rights movement which fought segregation in the synagogue, that began in the sixteenth century yet succeeded too late to save its people.

This is the end of history for the Jews of Kerala. Sixty years after the formation of the state of Israel, sixty years after the birth of the Indian republic, the clock is ticking for India’s oldest Jewish Diaspora, and it is one minute to midnight.

* * * *

So how did it begin? The available history is a patchwork of folklore, fable and historical fact. The Old Testament indicates that the first Jews landed on Indian shores thousands of years ago, sailing from Israel on trade missions from the court of King Solomon. Biblical accounts depict sailors and merchants docking at Kerala’s main harbor, charged with procuring spices and exotic treasure such as “elephant’s tooth, peacocks and apes”. A further wave of immigrants arrived after the Roman capture of Jerusalem and destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, a ruthless act of conquest which sent the Jews into exile, scattering their tribes across the globe like seeds of last hope to the winds.

This particular Diaspora never knew persecution in their adopted land. Instead, they were feted by Kerala’s rajas as foreign kings, lavished with land, privilege and autonomy. In return for privileges that included respect for the Sabbath, the right to use symbols of royalty such as parasols and gun salutes as well as protection from hostile invader forces, the Jews swore fealty to the Cochini rajas, fighting alongside their armies during battles with warring neighbors and acting as advisers at court. They were respected both on the battlefield and in the trading bazaar, seen as both valiant soldiers and astute merchants. As the turbaned raja held audiences in his chamber, seated aloft his silver throne or silk-upholstered day bed as the pankah-wallah gently fanned the regal presence, the Jews were periodically summoned, heads inclined in supplication, to this inner sanctum. The king would receive them in his palace in Mattancherry, which lies adjacent to the Paradesi Synagogue, evidence itself of the proximity of the Jews to their patron’s heart. The land on which the Paradesi synagogue and Jew Town were built was provided by the raja, a safe haven when they were driven out from their first city Cranganore. As a trading people, as people of letters and languages, through the centuries they stayed close to Kerala’s kings until India’s princely states finally ceded control to the Republic of India on Independence Day in 1947.

Yet more than two millennia since trade routes and the fall of Jerusalem first brought the settlers to seek sanctuary in these lands, this once illustrious people is now in its final days. To understand how, I began at the end, among the remaining White Jews of Synagogue Lane in Mattancherry and the Black Jews of Ernakulam’s Jew Town.

The district of Cochin is comprised of Ernakulam, the near

est thing to a big city which lies on the mainland’s coast and is less than an hour’s drive from the southern peninsula of Fort Cochin, and Mattancherry. Mattancherry also had its own Jew Town once, but today the community is confined to just a cluster of houses on a single street, with the rest of the village inhabited by Christians, Muslims and Hindus who bought up the Jewish homes piecemeal as the Paradesi community emigrated or died out. Separated by a rancorous past and a stretch of swamp-like water that crisscrosses the low-lying land and canals, the Black and White Jews have been compelled to come together in these final days.

This account—a mixture of interview and confession, archive and diary—charts their rise and fall, from a glorious centuries-long heyday when they were the confidantes of kings, to the twentieth-century decline and twenty-first-century denouement. Their fortunes were undone by a devastating nexus of apartheid, centuries of inter-breeding, mental illness and a latter-day exodus from Kerala after the creation of Israel in 1948.

This exodus proved to be a revival of sorts in the fortunes for the Kerala Jews in Israel. In returning to the place where it began, the narrative seemed to have come full circle, providing an ostensibly poetic conclusion for those who chose Israel over India. The majority were sent to live in the Negev. It proved to be a shocking adjustment: exchanging verdant south India for the barren beauty of the desert; a timeless and orthodox Jewish way of life for a secular and increasingly Westernized one; the security and ancient tolerance of Kerala for a life refracted through the deadly prism of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A few faltered as a result of change, withering once transplanted from their natural setting. Others thrived on the mighty challenge of Zionism, of making the desert of Abraham bloom once more. Akin to some Biblical parable, they grew roses and gladioli in the desert and initiated what was to become a major Israeli industry: horticultural exports. But perhaps, even more miraculous, family life prospered again as Cochini Jews married and raised children. In Israel at least, life has returned for the Kerala Jews.

The Last Jews of Kerala

The Last Jews of Kerala