- Home

- Edna Fernandes

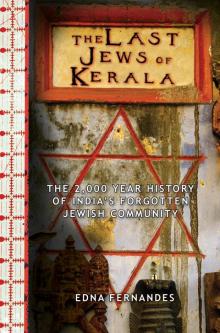

The Last Jews of Kerala Page 13

The Last Jews of Kerala Read online

Page 13

In India, politics is the route to not just lofty purpose, but also personal enrichment and aggrandizement. In an arena awash with dirty ambition, Salem had remained true to the values of his faith, to the importance of justice in the community.

I felt Gamy was being tough on his father, but as he himself recognized, perhaps this was because he felt he also failed to live up to his potential. Gamy had always dreamed of getting out, escaping, shaking off Jew Town’s strictures to explore a world that sang to his adventurous soul. He had the chance and he blew it. He could not forgive himself. Nor could he forgive his father, whose chances had been even greater.

“I find fault with my father, I find fault with myself,” he told me, in confessional mood that stormy afternoon just before the onset of Shabbat. “I went to the U. S., studied on a scholarship at Cornell, but came back here, got stuck, ended in same position. Same thing. Same fate. So who am I to criticize? But I did not have my father’s talent. I’m just an average person compared to him.”

“Aren’t you proud of your father’s efforts?”

“Of course I’m proud. But I would’ve been prouder if he’d answered the calls to greater things that kept knocking at his door. He ignored those calls.”

Despite choosing this path and renouncing the lure of national politics, Salem retained close relations with the Nehru dynasty which brought the Kerala Jews to prominent attention, once again enabling the community to punch above its weight for a little while longer. Gamy said one such example was when Nehru accompanied his daughter Indira Gandhi to visit the synagogue. The synagogue was even immortalized on an Indian stamp one year. Jew Town was a valuable symbol of India’s secular ideal, demonstrating its tradition of religious tolerance that stretched way back.

Down the timeline of Cochini Jewish history, there are moments that resonate through the millennia: the first contact with the kingdom of Solomon; the fall of the Second Temple; the arrival of Joseph Rabban on Indian shores; the loss of Cranganore and the arrival of the Jews from Europe who would initiate the divide between Black and White. In the late nineteenth century, the powerful advocacy of a Black Jew would restore Judaism’s ancient tradition of imparting justice. It was a legacy that was not his alone. Salem built upon the work of those before him, including his own grandfather, as well as unknown Jews, faceless heroes who fought for centuries to break the color bar of Jew Town. This was Cochin’s civil rights movement. Except, it started in the sixteenth century and did not conclude until America’s own campaign for equality was at its height in the 1950s and 1960s. The fight began where it ended in Salem’s time: in the Paradesi Synagogue, which was the focal point in the quest for equality.

* * * *

CHAPTER EIGHT

Segregation in the Synagogue

“You must not be guilty of unjust verdicts . . .

You must not slander your own people . . .

You must not bear hatred for your brother in your own heart . . .

If a stranger lives with you in your land, do not molest him . . .

You must count him as one of your countrymen and love him as

yourself—for you yourselves were once strangers in Egypt.”

—LEVITICUS 19:1—2, 11—18

After the loss of the Second Temple, the Jewish people were bereft. At first, they believed they had been abandoned by God. In the past the Temple represented the divine presence amongst them and as such it was the focal point of faith. Its destruction for a second time led the Jews to believe that it was wrong to cherish ambitions to resurrect the Temple a third time. After all, it was not Yahweh’s wish.

Instead they would find a new way to worship and in the end substitute the synagogue for the Temple in their day-to-day prayers: so the synagogue came to represent the lost Temple, a physical manifestation of faith at the centre of every Jewish community around the world. Its very structure emulated the hierarchy of the sacred chambers in the old Temple. The holy of holies, where Yahweh once resided, was evoked in the synagogue by the Ark which contained the Torah scrolls or Law of Judaism.

Shabbat was celebrated here, providing a new setting for the Jews to commune directly with the divine. The Shekinah or divine presence manifested itself wherever a minyan was formed. Through prayer they could welcome Yahweh in their midst again, wherever they may be, scattered as they were across the continents.

In this way the synagogue became the continuum of the Temple. Although it could never be supplanted in the Jewish heart, the synagogue was the nearest the people had to a link with God. Knowing this, one begins to appreciate the measure of anguish the Black Jews felt when they were told they were not equal before God in the synagogue. It was a rejection that struck at their very core.

* * * *

Rabbi ibn Zimra’s edict in 1520 marked the first tentative step in the arduous journey to equality that would take four centuries to travel. The Rabbi backed the Black Jews in their campaign, saying they did indeed have the right to intermarry and enter the synagogue as equals, provided all the proper conversion rituals had taken place. But the Paradesi leaders refused to budge and ignored the foreign Rabbi’s rulings.

A generation later, the Black Jews resurrected their campaign in another letter which was dispatched to a former student of ibn Zimra, Rabbi Jacob de Castro in Alexandria. After studying his teacher’s earlier missives, he reiterated that equality and marriage between the two groups were permissible. But again, the Paradesi Jews got round the situation by simply filing the letter into oblivion.

On the face of it, discrimination was targeted at the so-called meshuchrarim, or “manumitted ones”, referring to former slaves who were freed by their Jewish masters. In reality, though, the slave tag was used by the Whites to refer to anyone in the synagogue community they deemed to be non-white. The slur of slavery continued long after the British abolished the practice.

The Paradesis introduced a law that said their congregation did not recognize as equals children born from unions between white men and non-white women. A 1757 entry in the Record Book of the Paradesi Synagogue (page 82–83, according to Katz and Goldberg) sets the position out clearly: “If an Israelite or Ger (convert) marries a woman from the daughters of the Black Jews or the daughters of the meshuchrarim (manumitted slaves), the sons born to them go after the mother; but the man, the Israelite or Ger, he stands in the congregation of our community and he has no blemish.”

During these centuries, there were eight synagogues across Cochin, seven of which were used by the Black Jews. But the eighth synagogue, the Paradesi, was a bastion of white purity. Any Black Jews who lived in its proximity faced a ferocious battle for access. The Blacks were denied entry to the synagogue, denied the right to perform rituals there, banned from chanting certain liturgical hymns, banned from reading the Torah or scriptures, and prohibited from marrying into White Jewish families. All the above were seen as polluting acts which could taint the purity of the Paradesi community. Black families were barred from burying their dead in coffins or in the Paradesi Synagogue cemetery a few hundred meters away. In worship, love and even death, the color of a Jew’s skin determined his destiny. All these acts directly flouted Jewish law.

The Black Jews took on the discrimination one issue at a time. But the seminal battle was for equality in faith. For four hundred years, Mattancherry’s Black Jews were not allowed to sit on the benches of the Paradesi synagogue. Instead, they were relegated to sitting on the dirt floor of the anteroom outside the synagogue itself. From this lowly position they could hear services conducted by the White community. It was shocking to foreign observers even then.

Claudius Buchanan, a missionary who visited Cochin between 1806 and 1808 wrote, “It is only necessary to look at the countenance of the Black Jews to be satisfied that their ancestors must have arrived in India many ages before the White Jews.” He then added that despite this lineage, “The White Jews look upon the Black Jews as an inferior race and as not of a pure caste.”

&nbs

p; A modern-day observer, Rabbi Louis Rabinowitz, said in his writings in Far East Mission that the situation in Cochin was comparable to apartheid-era South Africa, where “irrational prejudices take precedence over law and logic and ethics.”

He noted parallels with South African apartheid in that whites were the dominant section of society even though they were a minority—representing one third of the local congregation in Mattancherry. If ever the segregation was challenged by the Blacks, the Whites would call upon the raja or local colonial powers to intervene on their behalf and quell any resistance.

The Blacks tried hard to resist and challenge the discrimination in the synagogue. Katz and Goldberg said a number of visiting foreign Jews also lobbied on the Blacks’ behalf for equality, but to no avail. By 1840,the Blacks found their situation to be intolerable and relations had reached a point where something had to give. Either the Whites must end the discrimination or the Blacks would rebel. In the end, it was rebellion.

The Blacks escalated the pressure, leading to the protestors being ejected from the synagogue community. Barred from worship even in the Paradesi synagogue anteroom, some of the Black Jews asked for permission to establish their own place of worship in one of the homes in Jew Town. The White leaders refused even this compromise. Following one particularly acrimonious exchange, the Whites enlisted the support of the local Diwan, who decreed that no prayer services be conducted by “the group with impurity in the house appropriated for that purpose” according to Johnson’s “Our Community in Two Worlds”. In a further insult, the Blacks were instructed by the Diwan to “walk submissively” to the White Jews, by way of contrition.

The “group with impurity” was led by a Black Jew called Avraham or Avo Hallegua, the grandfather of A. B. Salem. Who was Avo? One version of his history says that he was the son of a rich landowner Shlomo Hallegua and a woman named Hannah who was either born a slave or was the descendant of a poor foreign Jewish family. Either way, Hannah’s Jewish credentials were deemed dubious and not acceptable to the white community. Therefore, the marriage of Shlomo Hallegua and Hannah was not conducted in the synagogue but took place at his grand estate in Vettacka.

They conceived a son and Avo was born and grew up on the Hallegua estate. During this time, according to a document of manumission, Hannah was freed on the eve of Passover in 1826, with a stipulation that her sons be counted in the minyan. This act should have cleansed her of the past and accorded her offspring full rights in the synagogue. After this key event, Avo was given a full Jewish education and schooled in the teachings of the Torah.

But even a wealthy landowner like Hallegua was not impervious to the pressure of his peers. He was urged to marry a white woman. He did so and she also bore a son. When Hallagua died, Avo took over the estate and managed the business single-handed as his half brother was still a child. But once the child reached adulthood, the old order reasserted itself.

The younger brother, a White Jew, barred his brother from the ancestral estate and took his share of the inheritance. The Paradesis rallied to the younger brother’s side as the dispute became evermore steeped in bitterness. In the end, the matter was taken before the Cochini raja who ruled in favor of the white brother.

Avo lost everything. He was barred from his home and denied his share in the family estate which he had run since his father died. Overnight, he had become an outcast. Such a brutal rejection would have broken most men. But Avo was unlike others. He channeled the anger over his stolen birthright into a broader campaign: to take on the Paradesis directly, not over inheritance or land, but over the religious rights that had been denied to Black Jews like him for centuries. In his view, this was the most unforgivable of all the humiliations suffered by his people. It was the font of all inequality—the idea that the Blacks were somehow lesser Jews than Whites—the poisoned source from which all other injustices sprang. In this manner, Avo rose from being a disenfranchised landowner to Cochin’s first Black Jewish civil rights leader.

After the Blacks were banned from having their own separate synagogue in Mattancherry’s Jew Town, a group broke away and resettled in the British territory of Fort Cochin, a short distance away. There, they turned a private house into a synagogue and Avo took on the role of religious scribe or sofer as well as shohet. At first, their new community proved to be successful. The resettled Black Jews thrived and were integrated into the local community. They got on well with their non-Jewish neighbors and reports of those times showed the Black Jews as well-to-do. The Jewish women sported gold jewelry and their households even employed servants. Their revived fortunes contrasted sharply with their old rivals, the Paradesis, who were by this time considerably less well off.

But benevolence’s blessing on the Black Jews proved to be shortlived as disaster struck Fort Cochin. A cholera epidemic swept through their neighborhood and most of their number was wiped out in a matter of days. The devastated few that survived left for Bombay or Calcutta, where there were other Jewish communities, or returned to Mattancherry’s Jew Town.

The Paradesi leaders reveled in the misfortune of those who came back. They were told that if they wished to return to their old lowly position on the synagogue anteroom floor, they would have to pay a fine before being rehabilitated. The Whites saw the defection to Fort Cochin as an act of blasphemy and insurrection. One of the Whites was a man called Reinman who wrote about the whole sorry affair in “Masa’oth Shlomo b’Kogin”. He was actually fairly sympathetic, unlike some of the others, yet even he believed the Blacks had courted catastrophe through their ill-conceived defiance:

“God punished the sin of the (Blacks) who were disloyal and withdrew from the synagogue of the White Jews and desecrated its holiness . . . almost all of (them) died with the plague and epidemic . . . and many who remained became mad and got out of hand. The remainder of the refugees turned to the White Jews and paid a fine to the synagogue to accept them as before. Avo . . . died naked and for want of everything and his only son went out of his mind.”

That last line on the fate of Avo would have been a heartbreaking epitaph if that had been the end of the matter. But it was not. Avo’s true legacy was that he imbued a spirit of change in his people. That spirit remained undiminished even with his death.

In 1882, the Black Jews again asked the Diwan to permit them to worship in a private house. They sought the help of David Sassoon, a Bombay businessman, who wrote to the British Resident on their behalf. Again the plea failed. Disappointed and rejected, all they could do was keep going.

News continued to spread to the Jewish community overseas of the discrimination practiced in Cochin’s Jewry. Rabbinical emissaries arrived in India from Jerusalem to resolve the problem. Just as had happened 300 years earlier, the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem Rabbi Phanizel, ruled in 1882 that the so-called “slaves” should enjoy full religious privileges provided the special t’vilah ceremony was carried out. History repeated itself as the Paradesis again defied the Rabbi’s ruling. It seemed even the high-most authorities could not force the Whites to recognize the Blacks’ rights.

It would take the grandson and namesake of Avo to force the change. Where rabbis, elders and foreign emissaries failed, a low-born black lawyer from Ernakulam, A. B. Salem, would succeed. What Avo started, his grandson would finish in the following century.

With his birthright stolen, Salem did not have riches at his disposal, nor vast estates or privilege. But he did inherit his grandfather’s indomitable spirit and he was fired by the same zeal for justice. He used his law degree to fight the cases of the oppressed, not just for fellow Jews, but the lowest sections of society. For example, through the organization of trade unions, he helped low-paid workers such as the boatman improve their working rights.

His interest in grass-root politics eventually elevated him into the upper echelons of Cochini society, leading him to serve on the Cochin Legislative Assembly. In 1929 he was a delegate of the native Princely States of Cochin and Travancore to the nationa

l Congress meeting in Lahore where Gandhi launched his struggle for independence.

This was a turning point in Cochini Jewish history, as it was for Indian nationalism generally. It was here that Salem was converted to the gospel of Gandhian non-violent protest. He decided that if Indians could fight even the military might of the British using such methods, the Black Jews could deploy this same weapon in their struggle for equality in the synagogue.

Gandhi had used the tactic of passive resistance to successfully campaign on behalf of the Untouchables in neighboring Travancore. The Untouchables, now known as Dalits, were at the bottom of the Hindu caste system, had minimal rights and were ruthlessly exploited by the upper castes. On his return, an inspired Salem organized a satyagraha or non-violent resistance in the synagogue. He agreed with Gandhi that religious discrimination was “most pernicious” and was determined to end it in his own backyard.

Just as Gandhi’s empowerment through peace ignited the forces of a mass political awakening in India, so the “Jewish Gandhi” also succeeded in his small town revolution. The overturning of a tainted history began with one man staging sit-ins at the synagogue, using his oratory skills to advocate change and even at one stage, threatening to fast until death. Salem recruited his young sons—Raymond, Balfour and Gamy—to the cause, even though they were still small children. He would take his sons to the synagogue and refuse to sit in the designated space for the Blacks on the anteroom floor. Shunning this lowly position, he defiantly strode into the main synagogue itself, dragging his sons behind him.

One man who knew Salem in those heady days of protest was the father of Isaac Joshua, who is the current President of the Association of Kerala Jews and managing trustee of the Ernakulam Synagogue. Isaac, the foremost elder among the Cochini Jews, was now in his mid-eighties, but he had grown up on his father’s accounts of the Jewish Gandhi who was a close family friend. “I remember him too well,” he said, scratching his shiny copper pate as he summoned up its memories. “He used to come to our house every Saturday and spent Sabbath with us. He was my father’s great friend. He came to our house and synagogue for service and then he came for lunch every Saturday.

The Last Jews of Kerala

The Last Jews of Kerala