- Home

- Edna Fernandes

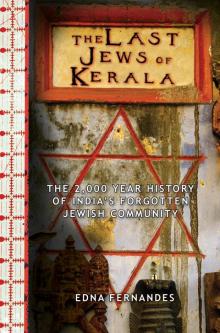

The Last Jews of Kerala Page 11

The Last Jews of Kerala Read online

Page 11

“Homeless, penniless, ignorant of the language of the country and unaccustomed to the scorching Indian sun, they took to agriculture and oil pressing. Their abstinence from work on Saturdays earned them the sobriquet of ‘Sabbath oil pressers’”.

In The Jews of India, published by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, their religious rituals are described as being “based on biblical Judaism: they celebrated Jewish holidays related to the Bible; the Sabbath was strictly observed; all male children were circumcised eight days after birth.”

Their guidance was provided by religious leaders called kazis, who officiated on Jewish matters and were often seen by local authorities as leaders who could deal with disputes. Initially, the community had no synagogue or Torah scrolls, replying purely upon their spiritual leaders.

By the seventeenth century, the British East India Company had established itself in Bombay, now called Mumbai. This acted as a catalyst for change as Bombay grew into the most important trading port in India and employment boomed, attracting thousands of people from across the subcontinent. One imagines the mood of expansion and boundless opportunity may be similar to the economic renaissance that India is witnessing right now, as millions migrate from the villages to the cities looking for a stake in the capitalist revolution.

In this same way, the Bene Israel people also migrated from countryside to the big city, drawn by the promise of an easier living. The community thrived. Many worked for the Company, with others enlisting in the military where several achieved high ranks and were awarded decorations for bravery. Others worked in construction or the bustling shipyards which furnished the trading boom of the British Empire with fleets to house Indian goods. The oil pressing tradition died out, eventually, as other players had already captured that particular market.

Their first synagogue, Sha’ar haRahamim, was founded in the city in 1796 by Commandant Samuel Ezekiel Divekar. He was something of a hero, being one of the few soldiers to survive captivity as a prisoner of war by the forces of the Sultan of Mysore. During his capture he made himself a promise: if he survived imprisonment, he would build a synagogue for the Bene Israel of Bombay. He had heard of them from his contact with the Jews of Cochin. The war hero was as good as his word.

The synagogue proved to be just the beginning and by 1838, the community had grown to 8,000—more than the Cochini and Baghdadi Jews put together. Eventually in 1875 a Hebrew-Marathi School was established in Bombay known as the Israelite School. As educational establishments such as these flourished, the level of literacy rose among the community and out of its numbers graduated advocates, physicians, engineers, accountants and civil servants. Yet the community was not entrepreneurial on the whole and preferred safe jobs, often in government services.

Relations in India’s cosmopolitan melting pot were good with the people of other religions in the city. Each community respected the religious practices of the other. As the community became established it started to use nearby Pune as a summer retreat. Others got jobs that involved them being stationed throughout the Indian empire, so the community branched out to new cities including Ahmedabad, Delhi and as far north as Karachi in modern-day Pakistan. However, these satellite communities were never more than a handful of Jews, and as a result did not register highly on the radar of the ruling Mughal powers of the north, where the dominant Hindus and Sikhs faced merciless persecution at times during this era.

While British rule endured, the educated Bene Israel did well. By the 1940s, the community had reached a peak of 25,000 people in India. The Bene Israel was like the Cochinis in that they also differentiated between fair- and dark-skinned Jews. This color distinction was also mirroring the indigenous society which put a premium on fairness. But the difference with the Bene Israel is their community to this day numbers thousands—evidence in itself of their ability to overcome their divisions in time and survive.

Also like the Cochinis, they too caught the attention of visiting foreigners who recognized them as a distinct people from the other Indians. One European Jewish traveler records his encounter in 1947. “Their garb and their complexion seemed foreign, but their eyes shining like little stars were as unmistakably Jewish as those of our boys in Poland who used to chant the Friday evening prayers with similar enthusiasm,” said Henry Shoskes in Your World and Mine. He was clearly moved to find these lost Jews in the heart of India.

“Choking with emotion, Cynowicz and I joined in the song. We did not mind the strangeness of the tune, the words or their meaning; the faith they expressed was the same as we have always known.”

The axis of events of 1947 and 1948—Indian Independence and the creation of Israel—would usher in irrevocable change, however. The Bene Israel became concerned for their economic prospects under the new political order in India as many had relied on the old British raj for their survival. Therefore, the combined lure of Zionism and new opportunities in Israel led many to leave forever.

* * * *

The raj proved pivotal in the fortunes of all the Jews of India. The rise of Bombay under the British led to Cochin’s eventual demise as the premier trading port of the west coast, which in turn impacted on the fortunes of the Jews there. In Bombay itself, the transformation taking place as a result of British trading led to the Bene Israel people migrating from village to city and tying their fortunes with the raj. In the case of the Baghdadi Jews of Bombay and Calcutta, they came to India from the Persian Gulf port of Basra which was another outpost of the British Empire around 1760. At this point, Jews involved in trade with India arrived from Basra and Baghdad, at first settling on the western coast of India. A community of one hundred Jews came from this part of the world to Surat, forming an Arabic speaking Jewish colony. These merchants were named Baghdadi or Iraqi Jews and in time others from Syria, Persia and Afghanistan joined them. Surat declined, leading important Jewish families such as the Sassoons, Abrahams, Ezras and Kadouries to move towards the new British-ruled commercial hubs of Bombay and Calcutta. Fortunes were made through trade in cotton, jute, tobacco and opium.

Within a century of their move to India the Arabic-speaking Jewish community numbered almost thirty families and the center of their religious life was a house rented from Parsis, who hailed originally from Persia. Thus, the old world and new conspired to survive.

The most famous of the Baghdadi Jews, whose name resonates in India to this day, is David Sassoon. He arrived in Bombay in 1833, the ancestor of the chief treasurer to the governor of Baghdad. He forged his own legacy in India as the head of a trading dynasty which would eventually stretch from Calcutta and Bombay to Shanghai and Singapore. He also became a renowned philanthropist which together with his commercial pedigree earned him the appellation of “the Rothschild of the East.”

Among his charitable activities was the building of the Magen David synagogue in Bombay in 1861, which included a religious school and hostel. Thanks to his company, Jews from across India found jobs in the Sassoon factories in Bombay. His corporate ethos was based on patrician values: he took it upon himself to provide food and accommodation for Jews arriving in the city, as well as arranging medical care and schooling for the children. The schools even taught ritual slaughter to ensure that families who were posted to remote areas far from other Jews could maintain their religious practices.

Sassoon’s contribution to Bombay life was acknowledged beyond his own people. On his death in 1864, the Times of India wrote that “Bombay has lost one of its most energetic, wealthy, public spirited and benevolent citizens . . .”

His successors continued his work of building a textile empire and also endowed charities, schools and built cemeteries for the Baghdadi Jews of Bombay. The second largest group of Baghdadi Jews settled in Calcutta, which was India’s eastern trading port. Many were Iraqis who had fled the tyranny of the Daud Pasha (1817–1831). The founding father of this branch of the Baghdadi Jews was Moses Dwek ha Cohen who served as head of the community, honorary rabbi and mohel, according to Th

e Jews of India.

They earned their living by becoming merchants in the lucrative trading of opium, silk, indigo and jute and by the nineteenth century had grown to some 1,800 people. A few worked in finance or become landowners. The Ezra and Elias families were dominant players here, like Sassoon, leading the way in employment creation as well as charitable activities.

I. A. Isaac described how the Ezras were drug barons of their day, exporting opium from Calcutta to South East Asia. David Joseph Ezra exported opium to Hong Kong, as well as dealing in more innocuous cargo. He acted as the agent for Arabian ships arriving at Calcutta to offload dates and other produce from Muscat and Zanzibar. Opium was merely one of many revenue earners in his commercial portfolio.

While the Baghdadi Jews were unsentimental in business, they were diligent in matters of religion. These same families helped build a series of synagogues, starting with the Neveh Shalom in 1831. In both cities, the Baghdadi Jews maintained their Iraqi Jewish traditions, as well as Arabic as their first language. They were well regarded by the British rulers and many were named honorary magistrates.

One unfortunate side effect of this closeness to the British was a negative attitude by the paler Baghdadis towards the indigenous Indians: “The Baghdadis wished to assimilate into British society and be considered European,” according to The Jews of India. As a result they aped European dress and lifestyle, as well as prejudices. The wealthier ones spoke English, not Hindi, Bengali and Marathi, the local Indian languages. They sought to join the stuffy and elitist English clubs—a bizarre little world of afternoon tea and dainty sandwiches, with cricket on the lawns followed by cocktails on the terrace: an Anglicized haven where the Brits could convene in private, away from the riff-raff natives.

The Baghdadis taste for social stratification extended to their fellow Jews. While Cochin’s White or Paradesi Jews were warmly accepted by them, the darker skinned Malabari and Bene Israel Jews were not. It mirrored the attitudes of the Paradesis in Cochin who also sought to play up their fairness, Jewish purity and European savoir-faire in order to court the approval of the ruling elite.

For the Baghdadis, this affiliation to the old raj spelled doom when the sun finally set on the Empire in India. As a result, after Indian Independence in 1947, the Baghdadi Jews found their position uncertain. The Socialist inspired government of the new India ushered in import and foreign exchange controls which hit the Jews’ business hard. The formation of Israel in 1948 also gave birth to an era of Arab-Israeli tensions in the Middle East, which further impeded the trading opportunities of the Baghdadis. For example, the key markets of Iraq and Egypt were both closed to their trading activities. By the 1940s, the once-invincible Sassoon family closed its factory gates, making thousands of Jews unemployed. By 1973, the mills of the Elias family in Calcutta had also shut down.

The result was economic misery followed by exodus, with many going to Israel or to the West to start over. By the mid 1990s, a community that was 5,000 strong in its heyday had collapsed to less than 200, a decline as precipitous as the Cochinis. Yet unlike their South Indian coreligionists, the Baghdadis never preserved in tact their identity once they moved overseas. It seems the Baghdadis at least, are in this sense, a lost tribe for sure.

* * * *

CHAPTER SEVEN

Son of Salem

“Courage has never been known to be a matter of muscle; it is a matter of the heart. The toughest muscle has been known to tremble before an imaginary fear. It was the heart that set the muscle trembling.”

—GANDHI, 1931

Every town has its maverick. In Mattancherry’s Jew Town that man was Gamy Salem: self-confessed cynic, scourge of convention and one who viewed the Cochini Jews’ checkered history with an unsparingly critical eye. He came from one of the Cochini Jewry’s most distinguished dynasties, a family of iconoclasts. His father had been known as the “Jewish Gandhi.”

The elder Salem had five children: two daughters and three sons. The sons, Raymond, Balfour and Gamy, all inherited the Salem spirit, but only Gamy survives still. In the 1950s, Gamy’s brother Balfour defied the conservative White elders by marrying Baby Koder, daughter of a prominent White Jewish family. It was the first intermarriage and blew apart the old dividing line. In a way, he was continuing his father’s work of breaking down barriers. Where A. B. Salem had used the law and nonviolent protests like his mentor Gandhi, his son Balfour changed local history by standing by his love for Baby.

Gamy also followed his brother in marrying a White Jewess, Reema, although things were much easier by the time their turn came. Sitting in his front parlor on Synagogue Lane, we would speak for hours on end. I came to enjoy our afternoon interludes over glasses of fizzy Mirinda and snacks. “Jew Town’s sole skeptic” as he called himself was a welcome relief from the prickliness of some of his neighbors. His approach to life was not bound by the strictures of orthodoxy and status. One sensed that for Gamy the world held deeper pleasures, more sparkling sensations than those of the synagogue and tradition. Here was an old man with a taste for trouble and an appetite for wider possibilities in life, even now, in his eighth decade.

When it came to his community, he feigned indifference, even amusement at this narrow little world, yet clearly he was deeply bound to it—despite his best efforts to disguise the fact that he cared. He remained one of the few willing to confront the past and future honestly. As one of the Black Jews in Ernakulam put it, “Gamy’s the only fellow over there who’s not a damned fool.”

Indeed, he was no fool, although sometimes he liked to play one. He was funny and kind with it. Strangers were drawn to his door by the tantalizing delights of easy conversation, bad jokes, worse whisky and fizzy drinks that glowed like radioactive waste. Seeing me stalking Synagogue Lane day in, day out, amused him. He would watch me from his doorway, feign horror, pretend to hide and then tease: “Your Enemy Number One (Sammy Hallegua) has gone to the market. I can talk for two minutes, then I have an urgent appointment to play bridge with my old ladies in Fort Cochin.” He wasn’t kidding about timing conversations. If he said he’d give you two minutes and gave you fifteen, next time you came by, he’d tell you that you were already in debt with him and he would not extend any more credit. I couldn’t help liking him and his wife.

A handsome man with the darker complexion more common to Keralites than the almost translucent fairness of the White Jews, he had a head of steel grey hair, and sported the local dress of short sleeved shirt hanging loosely over a white cotton checked lunghi tied at the waist. Reema was still a great beauty, with a flawless milky complexion, smooth forehead and the clear bright eyes of woman years younger. Together, they were a striking couple. So opposite in looks and temperament, yet like all really happy couples, when together they were seamless. They seemed to be relatively untouched by the melancholy that permeated the neighborhood, although there were times when they too succumbed.

Their home was simple, with a long corridor-style living room that opened straight onto the street through shuttered doors. Through to the right was another room, a dining area, with table and chairs, a fridge and walls adorned with huge framed family photos, including one of A. B. Salem. Black and white stills of the Jews in their heyday, dressed up and partying as well as shiny, bright snaps of grandchildren. Their Christian servant Mary, a diminutive old lady standing at four feet ten inches and dressed in a floral kaftan, would hover in and out of the living room as she went about her chores. She had just had her cataracts removed, paid for by her master. Rather incongruously, she wore glamorous Jackie Onassis style dark glasses that engulfed her tiny features as she polished and tidied and went about her work. Now and then she would come over to us and stand with one leg cocked coquettishly behind her, as she listened with her head to the side, even though her English was minimal. Her ease echoed that of her employers, for this was a happy house. And the master was never happier then when playing mischief. It was his chief pastime on a street where little happened any

more. He had a keen eye for comedy and would gather scurrilous scraps of gossip and feed these tidbits to his wife and friends. Nothing was sacred or exempt from his humor, not even the synagogue. Pomposity, greed, vanity were favorite targets.

One afternoon, as I took my habitual rest in his front room, a couple of visitors going to Sarah’s house caught Gamy’s attention. The unwitting prey for his caustic wit was a father and his sixteen-year-old son. They were converted Christians from Chennai, from across the state line in Tamil Nadu. Gamy began to tell me their story, his right hand occasionally lifting to his mouth as if to suppress a guffaw.

“See these two here. I call them Fool Number One and Fool Number Two. They’re low caste Hindus who converted to Christianity. Why? They were poor people and they thought it would bring a better life. Only thing, nobody got rich from going to Church. They hear about the White Jews. Old people, big houses and no children. Understand?”

I looked at this poor couple, wreathed in sweat as they struggled down the street with numerous heavy bags of food shopping, and felt an instinctive dread about their story.

“They come to Jew Town, they meet Sarah. They become friends. Our Sarah’s no fool, unlike our visitors from Chennai,” he sniggers, then sucks his teeth back in. “She tells them she cannot get quality vegetables in Cochin market, that the food is better in Chennai. So, every two weeks our friends come by train across the mountains, carrying heavy bags of Sarah’s favorite fruit and vegetables. From Chennai. For free!”

The Last Jews of Kerala

The Last Jews of Kerala